traditional forms of academic and professional research." width="502" height="472" />

traditional forms of academic and professional research." width="502" height="472" />Participatory approaches to research and evaluation intentionally include the people and groups who are most affected by an inquiry in the design and execution of the process. Participatory forms of research and evaluation help to ensure that the methods and findings reflect the perspectives, cultures, priorities, or concerns of those who are being studied. Because students, parents, community members, or other stakeholders are given active roles in a participatory research or evaluation process—and therefore roles in producing new knowledge or insights about their school, organization, or community—participatory research is a foundational and widely used strategy in organizing, engagement, and equity work.

While participatory approaches to research and evaluation can take a wide variety of forms, and many different methodologies (both quantitative and qualitative) may be used to achieve different objectives, participatory approaches to research and evaluation can be organized into three broad categories:

Participatory approaches to research, action research, and evaluation are based on similar philosophies, theories, and methods. For example, they start with many of the same underlying assumptions, such as:

In addition, both participatory action research and participatory evaluation are rooted in similar social-justice theories, especially theories related to the democratization of knowledge, which refers to the perspective that individuals and groups have the right to construct their own narratives, produce their own knowledge, and make sense of their own experiences.

This introduction will discuss the two forms of participatory research that are most accessible to local leaders, organizers, and practitioners involved in organizing, engagement, and equity work: participatory action research (PAR) and participatory evaluation (PE).

One of the more influential definitions of participatory action research was developed by Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury, editors of The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice:

“Action research is a participatory process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes. It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities.”

Participatory action research and youth participatory action research are a subset of the broader field of action research, which Richard Sagor, author of Guiding School Improvement with Action Research, defines as:

“A disciplined process of inquiry conducted by and for those taking the action. The primary reason for engaging in action research is to assist the ‘actor’ in improving and/or refining his or her actions.”

Reason and Bradbury provide further elaboration on participatory forms of action research:

“Action research is a family of practices of living inquiry that aims, in a great variety of ways, to link practice and ideas in the service of human flourishing. It is not so much a methodology as an orientation to inquiry that seeks to create participative communities of inquiry in which qualities of engagement, curiosity, and question posing are brought to bear on significant practical issues. Action research challenges much received wisdom in both academia and among social change and development practitioners, not least because it is a practice of participation, engaging those who might otherwise be subjects of research or recipients of interventions to a greater or less extent as inquiring co-researchers. Action research does not start from a desire of changing others ‘out there,’ although it may eventually have that result, rather it starts from an orientation of change with others.”

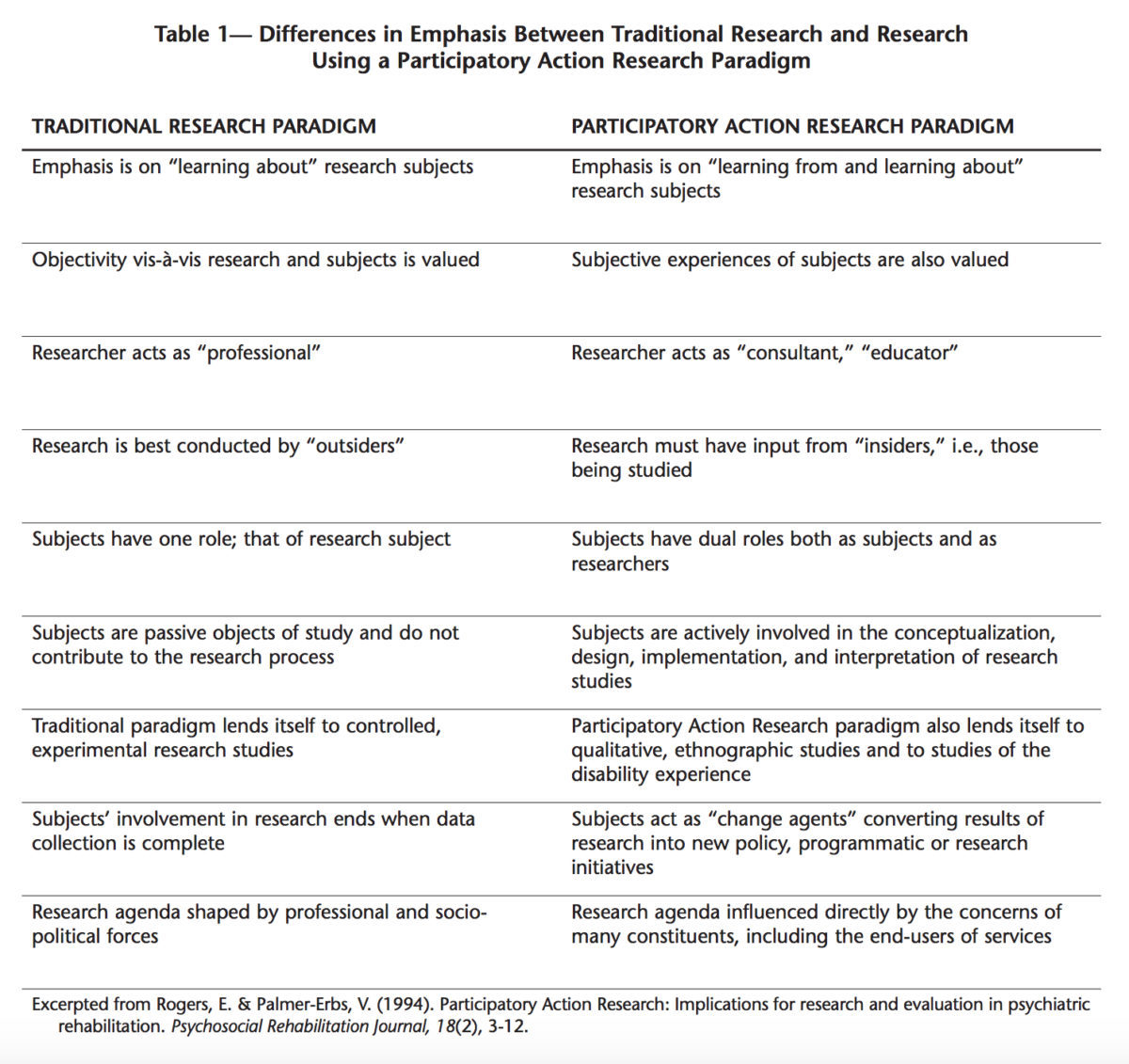

In formal academic contexts, action research and participatory action research are often contrasted with more traditional research approaches—specifically positivism and interpretivism—that are typically conducted by independent academic or professional researchers who do not involve “subjects” in the design or execution of the research process. While traditional research studies usually culminate in a written report of findings, and PAR projects often do as well, a primary objective of participatory action research is to effect change in a community, organization, or program or to improve the practice and effectiveness of individuals and teams.

While there are multiple—and sometimes conflicting—definitions of the two related concepts, action research generally refers to processes that are undertaken largely or exclusively by professionals, such as teams of school administrators or teachers. That said, some scholars or practitioners may use the term action research when describing forms of research that are considered participatory action research to others.

In certain contexts, participatory action research may also be called critical participatory action research, community action research, or community-based participatory research, among other terms, and different terms may represent divergent philosophical or methodological approaches to PAR.

traditional forms of academic and professional research." width="502" height="472" />

traditional forms of academic and professional research." width="502" height="472" />

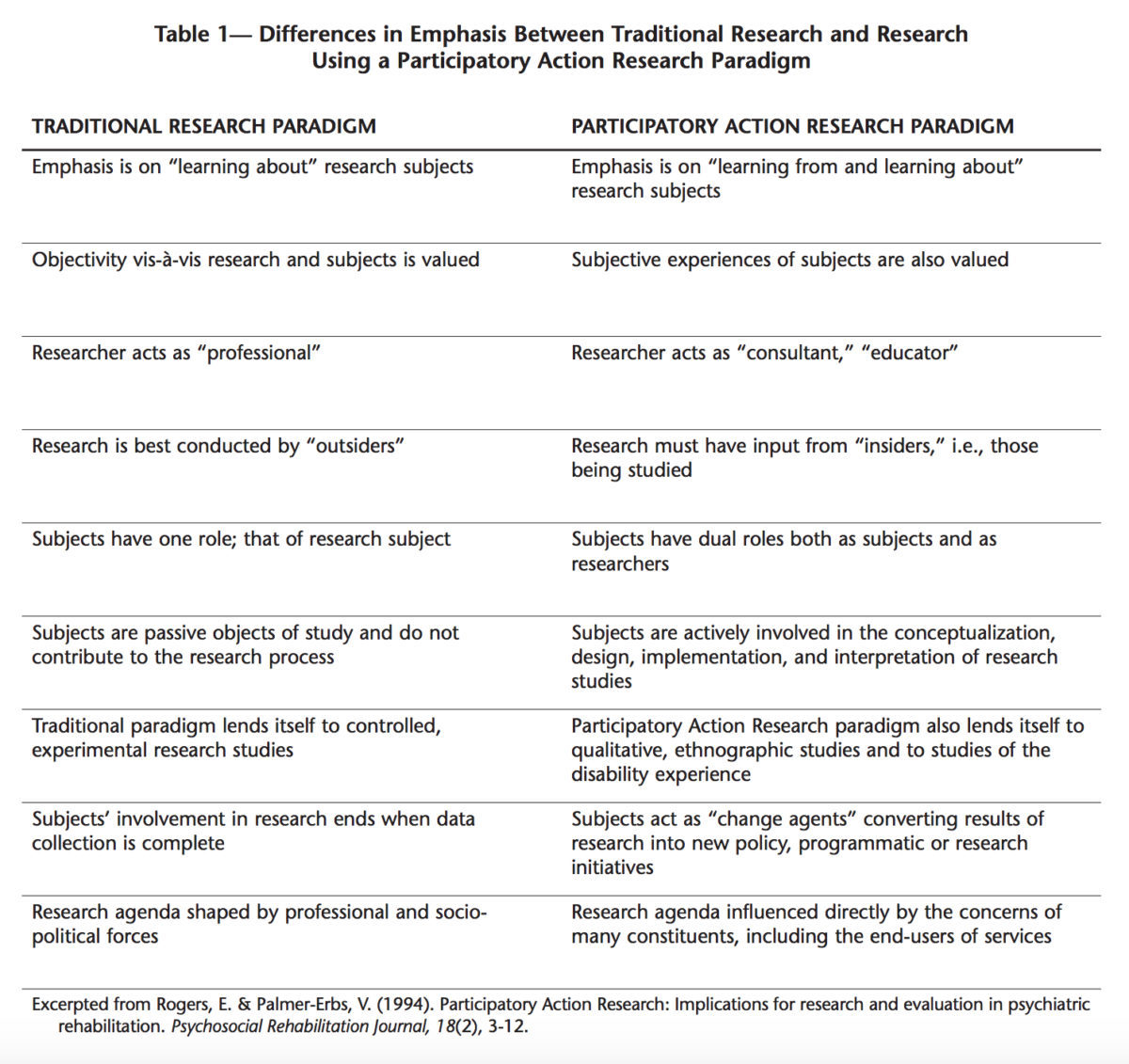

The primary distinction between participatory evaluation and participatory action research is that “PE” typically studies the implementation and impact of a specific program or process that has already been developed, while participatory action research typically investigates larger community issues or problems to inform the development of a new or emerging program or process. Both PAR and PE study past and current events to directly inform and influence future events.

In an influential 1998 article, “Framing Participatory Evaluation,” J. Bradley Cousins and Elizabeth Whitmore proposed two primary modes and objectives of participatory evaluation:

As Bradbury and Reason discuss above, participatory action research is “not so much a methodology as an orientation to inquiry.” That said, participatory action researchers and evaluators utilize a wide variety of formal and informal research methods, whether it’s quantitative research methods such as statistical analyses or qualitative methods such as observations of group interactions that are documented and analyzed to reveal themes, patterns, and insights.

Regardless of the specific method being used, a participatory action research or evaluation process always includes stakeholders—i.e., those who are involved, served, or affected—in the design and execution of the process.

A few common methods include:

Given that participatory action research can take a wide variety of forms, any concise description—such those above—is likely to omit important elements or methods. The following descriptions will help illustrate a few common features of participatory action research—features that also apply to participatory forms of evaluation.

To help put these features in context, the descriptions below also include case examples that illustrate how a PAR process might work in a real-world educational context. In this hypothetical case, a public school—”Sample High School”—is exploring new ways to approach student discipline because behavioral problems and disciplinary rates have been increasing for a few years.

In a participatory action research process, those who are affected by a problem, served by a public program, or employed by an organization have roles in each stage of the project’s execution. For example, participating stakeholders will be involved in the initial identification of the problem to be studied; the design of the research process or methods; the collection, documentation, and analysis of data; and the implementation of new approaches that result from the insights, lessons, and findings that emerge from the research. A participatory action research process is fundamentally inclusive and democratic, and the most effective projects involve a diverse and representative cross-section of staff and stakeholders.

CASE EXAMPLE: Historically, Sample High School administrators made unilateral decisions about disciplinary policies and their enforcement based on social traditions, subjective perceptions of what worked or didn’t work, and an incomplete understanding of the causes of student behavioral problems, which were often based on flawed assumptions about students and families. As a result, disciplinary policies and practices sometimes changed, but the results of those policies only worsened over time. Once the problem became too severe to ignore any longer, the school’s administrative team decided to use a participatory action research process to help them better understand the problem. The administrators began by enlisting a team of student, teacher, and family representatives to help them develop and execute a plan.

In a participatory action research process, students, parents, or community members—i.e., those who would be viewed as “subjects” in a traditional research study—are enlisted as “co-researchers.” In a PAR process, community participants become collaborative researchers who either work alongside professional researchers and evaluators, or they become community-based leaders of an action-research project that involves other community members. The insights that emerge from a PAR process are therefore the products of a working collaboration, rather than the products of professional researchers working independently of those being observed and studied.

CASE EXAMPLE: Rather than simply change disciplinary policies in the school—and hope they produce better results—Sample High School’s administrators and stakeholder PAR team instead decided to develop a deeper understanding of why existing disciplinary policies were not working. The PAR team collaborated with a nearby university, and students, teachers, and family volunteers received training in group facilitation, data collection techniques, survey methods, and other action research techniques. The PAR team then developed a set of research questions that they posed to students, parents, and staff during focus-group discussions and in an online survey. A significant percentage of the school’s student, staff, and family population was ultimately involved in the process as a leadership-team member, focus-group facilitator, or study participant.

The goal of a participatory action research process is to improve a program, process, or practice or to solve real-world problems. In many cases, participatory action researchers will begin to address a problem during the execution of a PAR process, or they will immediately use PAR findings to change their school, community, or organization after the process is completed. The term action refers to the transformative goals of PAR, the active involvement of participants, and the real-world actions taken by participants during and after a PAR process. While the resulting “actions” may be tangible changes in policies, programs, or practices, a fundamental transformation in the beliefs, perceptions, or worldviews of the people involved is another common result of PAR. For example, people may realize that their perceptions of a community group are based on biased assumptions or they may recognize that issues they formerly considered to be personal problems, such as poverty or low academic achievement resulting from families and students not working hard enough, are linked systemic causes in society.

CASE EXAMPLE: When Sample High School’s students, families, educators, and administrators came together to analyze and interpret the PAR data, each group gained a new and more nuanced understanding of the problem—and of each other. It also became apparent that several relatively simple adjustments could be made to existing discipline policies and practices to improve interactions between students and educators. As these improvements were implemented, the PAR team continued to collect and study discipline data, while also educating themselves about alternative disciplinary practices that had been effective in other schools.

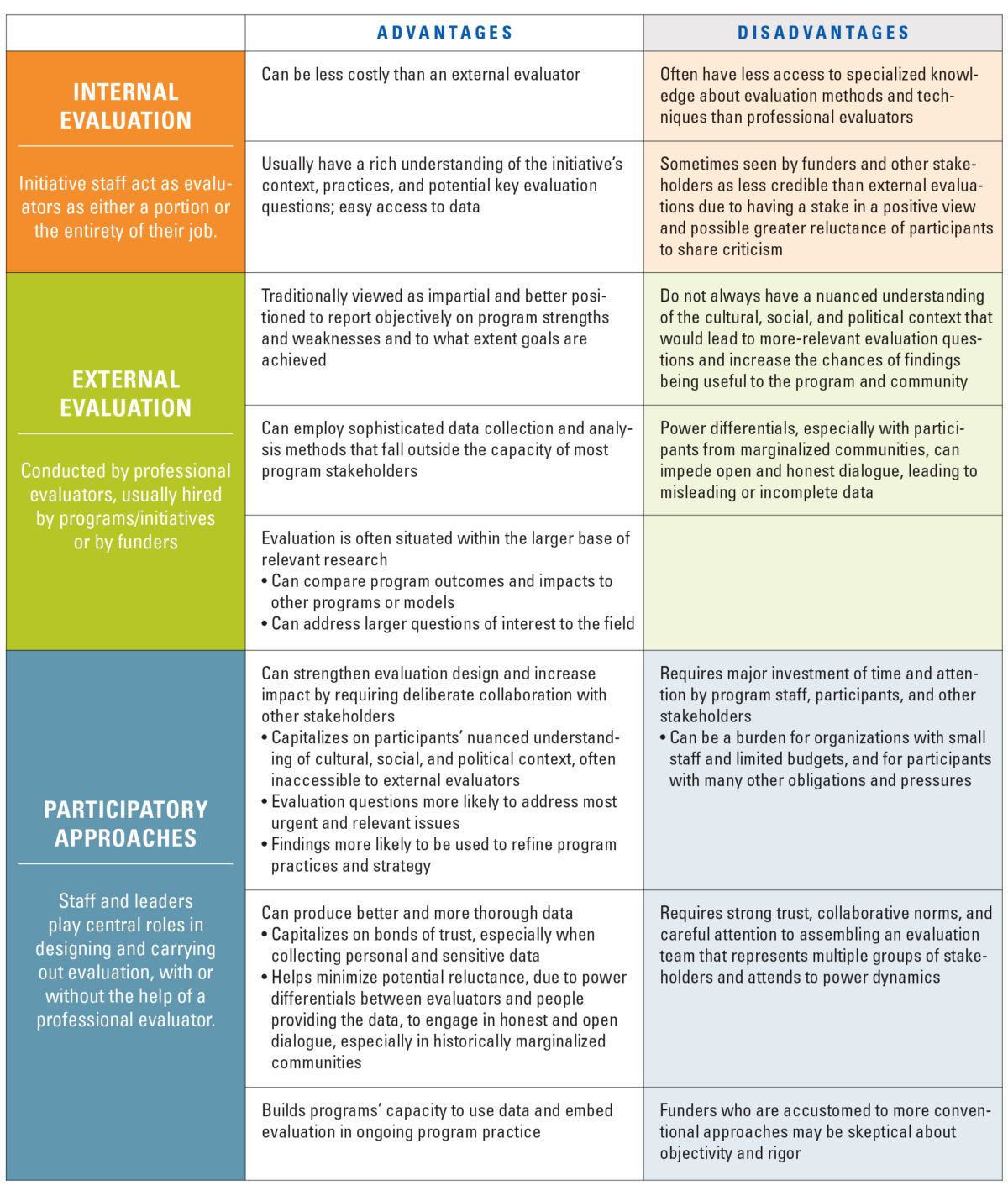

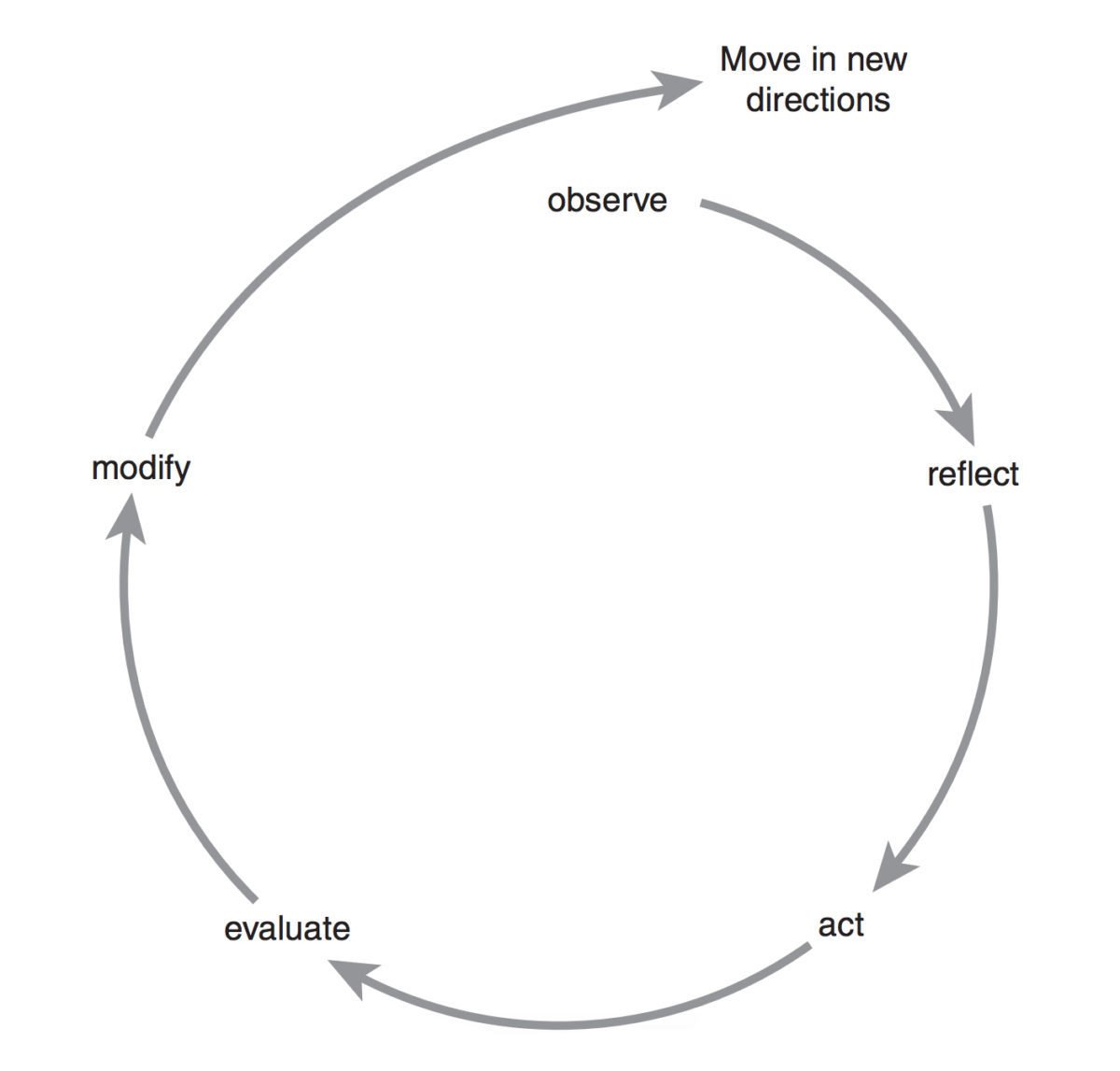

While a participatory action research process may have a defined start and end, PAR is often a method of ongoing practice and reflection. In these cases, PAR may follow a cyclical process of observation, reflection, action, evaluation, and modification (see image below), with each cycle yielding new insights or improvements. Similarly, participatory action research may also take the form of a series of connected research projects with defined start and end dates that cumulatively build on each other over time. PAR often begins with “small” cycles that address comparatively minor questions or problems before participants move on to more complex or consequential issues. PAR processes nearly always include stages of reflection, evaluation, or critical analysis, which extends to personal reflection and self-criticism—not just critical inquiry about external policies, programs, or practices. It is important to note that researchers and practitioners have developed numerous PAR models, and that different PAR models may recommend different stages or methods.

CASE EXAMPLE: Because Sample High School’s PAR data indicated that policy changes alone were unlikely to eliminate the problems surfaced during the focus-group conversations and survey, the PAR Team decided to follow a cyclical process of observation, reflection, action, evaluation, and modification. Over time, the school introduced policy modifications, a new staff training program, and alternative disciplinary practices, which resulted in a year-over-year decrease in behavioral problems and disciplinary referrals.

In a traditional researcher-researched relationship, the researcher is typically a highly trained professional who determines the goals of the process, how the process is conducted, and how the findings are interpreted, presented, or used. In this traditional scenario, researchers improve their skills, gain the most insights, and enhance their professional credentials—and they may also be the only individuals participating in a study who are compensated for their time.

In a PAR process, however, school, community, or organizational participants are given opportunities to acquire new skills and knowledge, and they are often compensated for their time, which can build their power, confidence, and personal sense of agency in a variety of ways. For example, participants may develop a deeper understanding of how their organization or community works, learn new skills that can be used in civic or professional settings, gain insights that help them more effectively advocate for themselves or for a cause, or acquire new information that reveals how they are being disadvantaged or exploited by existing policies or systems. Many advocates of PAR contend that the self-empowerment of stakeholders should not just be a side effect of a PAR process—it should be an explicit goal.

CASE EXAMPLE: Through their involvement in the action-research process, Sample High School’s students, teachers, and family members were able to connect disciplinary issues in the school to broader social issues related to policing, mass incarceration, racism, and poverty. Over time, the perceived source of the problem shifted: rather than focusing their disciplinary efforts on changing student behaviors, the school dedicied to enact policies and practices that countered—rather than exacerbated—broader social forces. Members of the PAR team not only gained new research, facilitation, reflection, and data-analysis skills, but they were also motivated to share what they learned during school-board meetings and community forums, which led to them acquiring new skills and confidence as advocates, presenters, and public speakers. In addition, multiple members of the PAR team decided to become more involved in their school and community, and two members decided to run for open school-board seats in the next election cycle.

Participatory action research is based on the premise that all knowledge is socially constructed, and that knowledge reflects the biases, priorities, or concerns of those who create it. Consequently, those who control how knowledge is produced or understood can exert power over those who do not participate in the creation of that knowledge. Because new knowledge or information is socially produced, it can also perpetuate harmful social behaviors such as stereotyping or discrimination. Participatory action research can therefore challenge, mitigate, or disrupt real or potential social problems by including historically marginalized, disadvantaged, silenced, or oppressed groups in production of new knowledge—knowledge that, as a result of their participation, is more likely to reflect their cultural experiences, perspectives, priorities, and concerns.

CASE EXAMPLE: During the PAR team’s focus groups, Sample High School’s administrators and educators were surprised, and occasionally even shocked, by what they learned from participants. They realized that the home lives of their students and families were far more difficult than they had assumed; that behavioral problems often began with stressful situations outside of school; that teachers didn’t have training or clear guidance on how to manage behavioral problems productively; and that many parents were looking for strategies to reduce the stress their children were experiencing inside and outside of school. School leaders began to see that policies and practices designed to control student behavior, rather than show respect and compassion, were contributing to the problem. School leaders also realized that they did not have the capacity or expertise to address some of the problems identified during the focus groups, and that they needed to enlist assistance from outside organizations and agencies.

Because a participatory action research process erodes the distinction between researcher and researched, it can challenge the assumptions or biases of researchers and leaders, just as it disrupts the traditional distinction between those who produce new knowledge and those who might either benefit from or be harmed by that knowledge. In some cases, the separation of researcher and researched can lead to a variety of negative outcomes, such as the wrong problems being studied (due to biased and flawed assumptions made by researchers), or the manipulation of research findings for the purposes of maintaining power, misrepresenting opponents, or advancing an agenda that may not be in the public interest.

Some advocates of participatory action research contend that when school, community, or organizational stakeholders are not involved in the production of new knowledge, the resulting information and interpretations are more likely to be inaccurate, misrepresented, or abused by those who control its production. In this way, PAR is often one of many strategies used to advance greater equity, justice, transparency, or accountability in programs, organizations, and public institutions such as schools. A PAR process is also intentional about acknowledging and disrupting inequalities of power among team members. For example, a PAR team might engage in an open conversation about how power and privilege affects their group’s dynamics and decisions, and about how they might structure their working partnership to ensure equity of voice, leadership, and decision-making.

CASE EXAMPLE: By giving up some degree of control over the research and decision-making process, and allowing their long-held professional assumptions to be challenged, Sample High School’s administrators not only became more informed about the problem, but they felt more motivated and empowered to address it. While the conversations were emotionally difficult for everyone involved at times, the PAR process ultimately helped administrators, teachers, students, and families learn how to be more honest and vulnerable with one another. Even though administrators felt uncomfortable and defensive at first, especially when students expressed their feelings about the school’s disciplinary policy or described their experience of being disciplined, the process resulted in a much clearer understanding of their students and families, which helped the administrative team build stronger and more meaningful relationships with their community that also led to positive changes in other school policies, programs, and practices.

As with any approach to research or evaluation, participatory forms of action research and evaluation are the subject of debates and criticisms, while the efficacy or outcomes of a particular PAR or PE process are often determined by how well or poorly it’s designed and implemented.

The following descriptions illustrate some of the challenges commonly encountered by local leaders, organizers, or practitioners implementing a PAR, YPAR, or PE process:

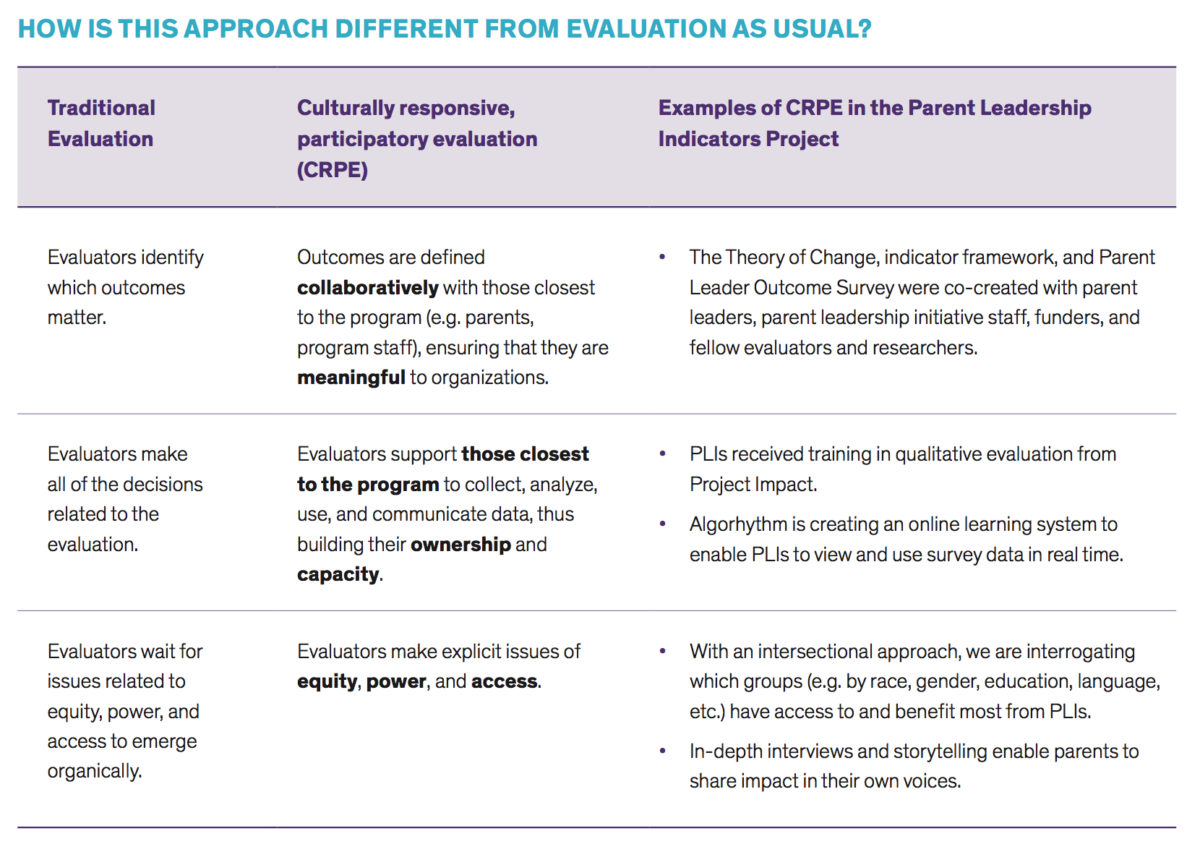

Organizing Engagement thanks Joanna Geller of the Parent Leadership Indicators Project at the Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools for her contributions to developing and improving this introduction.

Baldwin, M. (2012). Participatory action research. In M. Grey, J. Midgley, & S.A. Webb. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social work. (pp. 467–482). London: Sage Publications.

Cousins, B. J., & Whitmore, E. (1998). Framing participatory evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 80, p. 5-23.

Danley, K.S. & Ellison, M.L. (1999). “A handbook for participatory action researchers” in Systems and Psychosocial Advances Research Center Publications and Presentations. Boston: Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at Boston University. *Illustration

McNiff, J. & Whitehead, J. (2011). All you need to know about action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. *Illustration

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding school improvement with action research. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.